200 Million Years Ago, Life Bounced Back. Gastropods Show How

How long did ecosystems take to recover after the mass extinctions that marked the geological history of our planet? And through what dynamics did biodiversity reorganize itself? A useful piece of the puzzle for understanding these events has recently been published in Papers in Palaeontology by a team of researchers from the Department of Geosciences at the University of Padua and the National Museum of Natural History of Luxembourg.

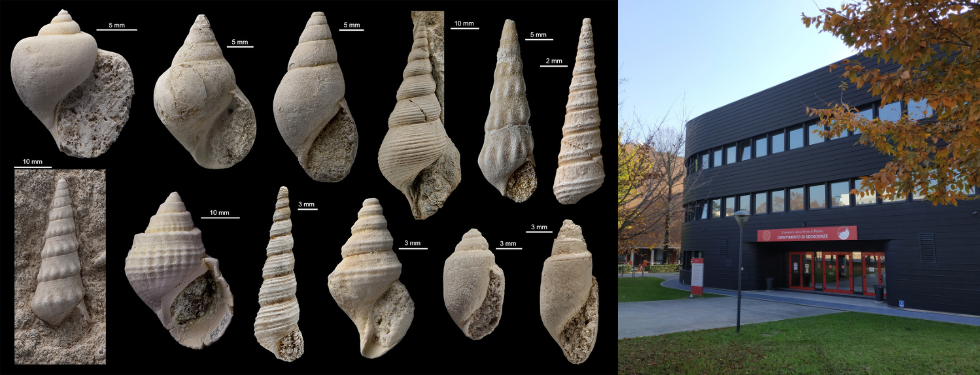

Starting from the study of a rich collection of gastropods housed at the Luxembourg museum, the researchers reconstructed the recovery dynamics of this group of marine mollusks after the mass extinction that occurred at the transition between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, around 200 million years ago.

The study, which also led to the identification of eleven new species, analyzed all the gastropod faunas that succeeded one another during the first 15 million years of the Jurassic in the western Tethys seas, a vast ocean that at the time stretched from what is now the Mediterranean region to the Far East. “This is a database of about 1,400 species that we assembled by studying numerous fossil collections from across Europe and then analyzed using statistical methods,” explains Stefano Monari from the Department of Geosciences and first author of the paper.

“We discovered that, at the beginning of the period considered, the sea that covered much of present-day northern Europe was inhabited by faunas different from those living farther south, along the northern margin of the Tethys. This was probably due to differences in the marine substrate on which the mollusks lived. This situation later changed when, following tectonic movements linked to the opening of the Atlantic Ocean and the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea, the geography of the western Tethys was reshaped, leading to the formation of new habitats that further promoted gastropod diversification.”

The research also quantified changes in the number of gastropod species in the critical interval following the end-Triassic mass extinction, showing that despite the severe losses suffered, the recovery of biodiversity in this group — the so-called “recovery” — was very rapid, at least on a geological timescale, confirming what is already known for other marine animal groups such as corals and ammonites.

“This clearly distinguishes this extinction from the earlier one that occurred 250 million years ago, at the end of the Paleozoic, which caused the near-total disappearance of life on Earth,” explains Roberto Gatto from the Department of Geosciences and co-author of the study. “In that case, the recovery of biodiversity, which lasted several million years, was much slower. The five major mass extinctions have represented turning points in the history of life on Earth, and each time the subsequent recovery of biodiversity required geological timescales. This should prompt reflection on the risks faced by today’s ecosystems, which, due to the impact of human activities, may be heading toward what many have defined as the Sixth Extinction.”

PRESS INFORMATION:

“Caenogastropods and heterobranch gastropods from the Hettangian deposits of Luxembourg: palaeobiogeography and Early Jurassic faunal recovery in the western Tethys”, Papers in Palaeontoly

Stefano Monari, Roberto Gatto, Mara Valentini, Robert Weis